It was great fun to be a guest at the Official Residence of the Consul General of Japan in NYC to celebrate the Capital of Japanese Food (self declared): the Tottori prefecture. Under a grey and crying sky ready to fall on my head I was more than happy to take refuge in the Carrère & Hasting early 20th century building for a gastronomic & cultural escapade. While being searched to the beat of light salsa music, the gaudy French Louis the something or other décor and the delicate Japanese paintings indicated a delightful juxtaposition of cultures. I knew nothing about the Tottori region, but I’m ready to go visit! To quote Wikipedia:

“Tottori Prefecture

(鳥取県, Tottori-ken?) is a prefecture of Japan located in the Chūgoku region on Honshū island. The capital is the city of Tottori. It is the least populous prefecture in Japan.

According to the brochures, the Tottori region offers an amazing variety of landscapes, natural resources & ancient cultures. From the legendary largest sand dunes of Japan, to the beauty of Mt Daisen, to the treasures of ancient Buddhist temples — and all this at the edge of Sea of Japan!

The short and convivial opening remarks by the consul & the governor were followed by an Ikizukuri demonstration/performance by master chefs from the Tottori region: Souichi Chikuma (executive chef at Ryokan Ohashi) and Tetsuyoshi Hada (executive chef at Kouraku). Ikizukuri means “prepared live,” and is the preparation of sashimi from a living animal. In this case the fish was already dead. The master chef skillfully carved the flesh out without damaging the exterior appearance of the fish (that reminded me of the first time I had to debone a quail without breaking the skin, not easy!) The fish was then set on bamboo sticks and adorned with an Ikebana style flower arrangement. The flesh cut into bite size sashimi was laid on top of the fish. While chef Chikuma worked on the huge red sea bass, chef Hada turned a large daikon into lace. We were told that this type of arrangement is very costly and done only for special celebrations like weddings.

On the second floor Tottori products were displayed for sampling. Tottori’s water is renown throughout Japan for its purity and richness, thus the quality of the local rice, sake, tofu and other products. I tasted delicious sakes from different grades of polished rice, though I need a few more tastings before I can really appreciate the sake subtleties. I was introduced to 20th century pear liquor and vinegar. They didn’t come from the same company but they were both interesting and I will certainly buy them when readily available. The 20th century pear grown in Tottori is the Nijisseiki variety; in Japanese Nijisseiki means “20th century”. I would assume that the link between the name and the date comes from the fact that the cultivar was created in Japan in1898.

On the second floor Tottori products were displayed for sampling. Tottori’s water is renown throughout Japan for its purity and richness, thus the quality of the local rice, sake, tofu and other products. I tasted delicious sakes from different grades of polished rice, though I need a few more tastings before I can really appreciate the sake subtleties. I was introduced to 20th century pear liquor and vinegar. They didn’t come from the same company but they were both interesting and I will certainly buy them when readily available. The 20th century pear grown in Tottori is the Nijisseiki variety; in Japanese Nijisseiki means “20th century”. I would assume that the link between the name and the date comes from the fact that the cultivar was created in Japan in1898.

One regret was not to get to try the star crab of Tottori, the Matsuba crab also called Queen crab or snow crab, it is a winter delicacy that was on display (frozen) but not for tasting. We got to try the delicious white squid served raw over a cup with a light broth; a most delicate colored trio of Aji —horse mackerel— wrapped in ribbons of radish, carrot and cucumber.

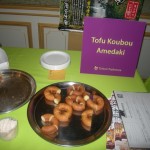

I cannot describe everything I ate as I am running out of time and I will conclude with Tofu Koubou Amedaki, a tofu doughnut! I was not going to try it, but being a fried dough fan I couldn’t resist and I am glad. It looks like a doughnut but tastes like a heavenly doughnut! Very soft inside, crunchy outside, not overly sweet & made with fresh soy milk.

Tottori came to me, now I need to go to Tottori! And thank you Shigeko & Miguel from La Fuente Services & of course Chiaki!